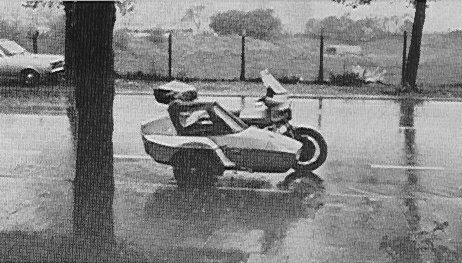

Moto Guzzi I-convert / Moturist combination.

Guus van de Beek, journalist of the Dutch journal "weekblad MOTOR" borrowed Ed Pols' personal rig for a training run for the autumn-rally Liege - Nice - Liege in spring 1978. His wife and daughter came along for the ride.

Previously published (in Dutch) in weekblad MOTOR, June 28, 1978

By GUUS van de BEEK (English translation: Gerard Geertjes)

For me as a motorcycle journalist it is inevitable to critically evaluate the motorcycle that I’ve been riding for such a long distance. However, evaluting a motorcycle-sidecar combination is not easy, because the designers’ philosophy is an important determinator of the riding characteristics. For instance, a combination like Bilands’ BEO would do much better on the road (such a machine has actually been designed in Germany, around a VW engine/gearbox unit), but of course this can hardly be called a motorcycle with sidecar. Hennie Winkelhuis at EML goes quite far: he builds completely new frames for motorcycles that originally are not very well suited to be combined with a sidecar, but he deliberately chooses for asymmetry: single wheel drive, and no brake on the sidecar wheel.

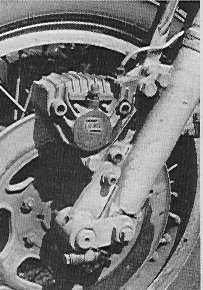

Ed Pols has a puristic approach to motorcycles. To him a motorcycle with a sidecar is just that: a motorcycle with a sidecar. If desired, it should be possible to ride the motorcycle solo without spending too many hours of work. Adaptations are okay, and anything goes to improve the qualities of the sidecar itself. That’s why the Moturist is equipped with a disc brake that is hydraulically coupled to the bike’s brake system, and adjusted so that the loaded rig remains well on course even during very powerful braking. That worked very well. We’ve driven other combinations that were equipped with a sidecar wheel brake; without a doubt this one was the best, although the brake pedal needed quite a lot of pressure.

Much attention was given to the Moturists’ suspension and shock absorption. The wheel-swing arm is supported and braced over the full width of the sidecar frame. In combination with a very rigid four-point attachment this results in a very stable vehicle (that’s right, there’s hardly any need for a steering damper). A torsion bar provides suspension, it's variable fixation enables adjustment of the spring tension. The Koni shock absorber is mounted separately in front of the wheel.

The combination of the Moturist with the Moto Guzzi Hydroconvert is aligned with rather little lean-out, and quite a lot of toe-in (50mm). The result is a wide speed range where the rig runs straight with hardly any steering corrections. With two passengers that differ about 20 kg in weight, the ideal situation was: on the motorway the wife rides pillion, and the daughter sits in the sidecar, and the other way round in the mountains.

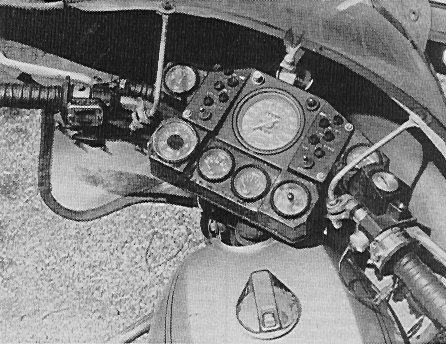

The steering forces of a sidecar combination are more or less proportional to the trail of the front wheel (swing effect). The trail of a Guzzi is about 95 mm, not that much, but really too much for a combination. Ed Pols cleverly designed a construction that shifted the front wheel axle 40 mm forward and thus effectively reduced the trail by the same amount. This effect too is very noticeably, although personally we would prefer a swing arm front fork. However, that doesn’t suit the chosen sidecar philosophy.

The passengers praised the sidecar's comfort. There is a slight draught from the left (because of the bike's wind shield?), but there is no need to wear goggles and smoking is no problem at all. There is a lot of leg room. Our entire luggage for a week fitted into the sidecar, so nothing was carried on the bike itself! The access to the (huge) trunk is rather narrow, and the finish is DIY (saw off small bolts, install lining).

After Lyon (translator's note: this” test” concerns a trip Liege – Nice v.v., click here for a trip report in Dutch) there was a rattle in the engine when running idle, apparently originating from the right hand cylinder head. Checking the valve clearance turned up nothing out of the ordinary, so we thought it might be the clutch. The cause appeared to be something completely different. The nut that fixes the distribution gear on the crankshaft had come slightly loose, the gear had a little play on the shaft and the camshaft could shift in respect to the crankshaft. This resulted in the valves hitting the pistons, leaving traces of one and a half millimetre deep, but at higher than idle revs the engine ran 1000 kilometres without a problem. Twice we added half a litre of oil and every 10.7 kilometre 1 litre of petrol ran through the nozzles. Solo motorcycles exist that use more!